Matt Taibbi Misexplains Crypto: Part 2

Dissecting "The Financial Bubble Comes Full Circle"

This is the second in a two-part series responding to Matt Taibbi’s recent Substack articles about crypto. He wrote two pieces on the topic: One that focuses on concerns regarding Circle - issuer of the popular stablecoin USDC - and another that discusses how crypto’s purportedly failed effort at decentralization makes it just another “great American bubble machine”.

These are both subjects worthy of discussion. But I found Mr. Taibbi’s treatment of them to be lacking and ultimately demonstrative of the limitations of journalistic tourism (i.e., when a non-expert attempts to understand complex topics and reports on conclusions derived from superficial knowledge).

The first piece in this series took on Mr. Taibbi’s post entitled “Return of the Great American Bubble Machine”. This one will focus on his other piece entitled “The Financial Bubble Era Comes Full Circle”.

Having convinced himself that CeFi entities are destroying crypto’s DeFi ethos, Mr. Taibbi took aim at Circle as being worthy of suspicion. As mentioned, Circle is the issuer of USDC, today the second-largest stablecoin in circulation.

Stablecoins are designed to be pegged 1:1 to a stable asset. Their aim is to give crypto users a native “reserve” asset that couples price stability with on-chain operability to facilitate transactions across the digital asset ecosystem.

There are three main types of stablecoins: 1) fiat-backed (collateralized by USD, EUR, etc.); 2) crypto-backed (collateralized by BTC, ETH, etc.); and 3) algorithmic (whereby a peg is maintained through a decentralized arbitrage mechanism). The crypto highway is littered with the corpses of failed stablecoin projects, the most recent and spectacular being TerraUSD (UST), which was discussed in part one of this series.

Virtually all stablecoin failures have been of the algorithmic variety. The goal of these projects is admirable in that they attempt to make their functioning as decentralized as possible. The impetus for this was brought into stark relief last week when Circle froze over 75,000 worth of USDC linked to the recently-sanctioned privacy coin Tornado Cash. But despite their noble intentions, algorithmic stablecoins have proven inadequate to the task with death spirals proving more an inevitability than possibility.

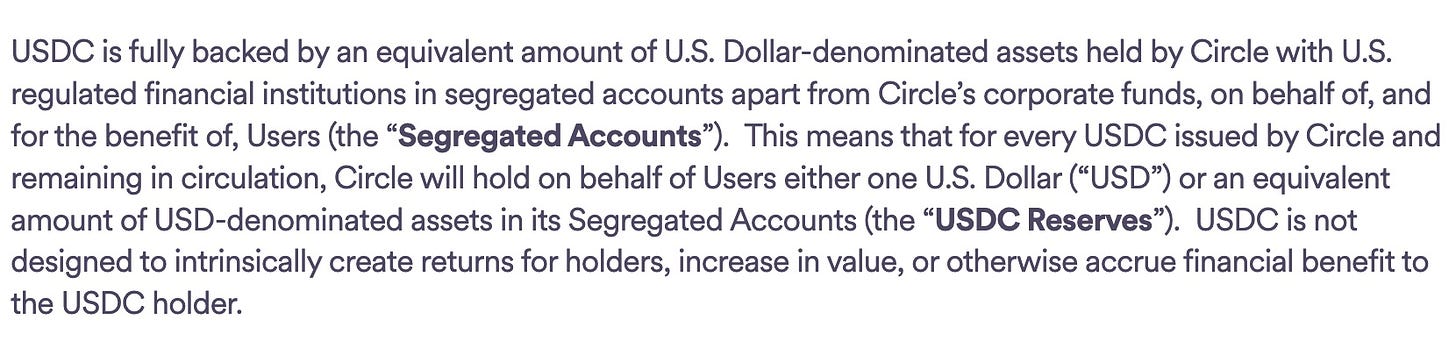

The two largest stablecoins - Tether (USDT) and USDC - are fiat-backed. These issuers basically take $1 from a user in exchange for an equivalent stablecoin unit and strive to ensure that their coins can always be redeemed by that user for $1.

The primary way that groups like Circle and Tether make money is through investment income generated by their reserves. Put simplistically, if there are 100 USDC in circulation, Circle has $100 in reserves upon which it can earn interest.

Given this arrangement, groups like Tether and Circle leave themselves open to the potential for asset-liability mismatches. This is somewhat similar to what we saw with Celsius et al, so it’s understandable why Mr. Taibbi might be concerned.

But there is a meaningful difference in business models that should be noted. In the case of a shadow bank like Celsius, the business involves taking customer deposits in exchange for yields that sometimes approached 20%. One can imagine the risk involved in achieving such high yields, which came home to roost in recent months.

In the case of stablecoins, users are offered 0% returns. This means stablecoin issuers are not incentivized to assume outsized risk in a reach for yield. They just need to ensure they can take $1 and return that $1 anytime thereafter.

Also interesting is that Mr. Taibbi chose to focus on USDC rather than the much-maligned USDT, which is no stranger to controversy. I respect his willingness to bypass the low-hanging fruit of stablecoin qualms, though I wonder if his decision to cut against the grain forced some manufactured beefs.

For Mr. Taibbi, the trouble started with the revelation that BlackRock would join Fidelity and others investing $400 million as part of Circle’s latest funding round. Most problematic to Mr. Taibbi was the announcement that BlackRock would become the primary manager of USDC reserves in what is called the Circle Reserve Fund.

Sources called with concerns. The fund’s registration statement says “shares are only available for purchase by Circle Internet Financial, LLC.” Not only is this unusual — one legal expert I spoke with said he’d “never seen such a fund… available for sale solely to a single entity”

Despite the apprehension of Mr. Taibbi’s sources, it’s become increasingly common for asset managers to launch funds with a single investor. These products typically come in the form of a separately managed account or a Fund of One. Investors in these vehicles tend to be big enough to dictate their own terms and mandates. It strikes me as reasonable that Circle - with a $40 billion-plus reserve management mandate - would be able to command such accommodation.

Mr. Taibbi’s primary concern appears to be the issue of bankruptcy remoteness. This relates to the potential that USDC reserves could be forfeited should Circle ever go bankrupt. This ties back to his other piece, which highlighted the perceived risk that user assets could be confiscated in the event of a Coinbase bankruptcy.

It’s at the core of the whole dilemma of the cryptocurrency markets. Certainly the question of who actually owns and controls reserve assets exists, or seems to exist. Here Circle is unlike some competitors, whose user agreements specifically spell out that reserves are, say, “fully backed by US dollars held by Paxos Trust Company, LLC,” or “custodied pursuant to the Custody Agreement entered into by and between you and Gemini Trust Company, LLC.” Those describe trust agreements, which are truly bankruptcy remote.

A couple of things here. First, crypto has many worries and dilemmas; I reckon the financial stability of Coinbase and Circle does not sit at the core of any of them.

Second, Gemini is in the custody business…of digital assets. The company does not custody fiat for the purposes of its own stablecoin, Gemini Dollar (GUSD). It instead outsources that function, just as Circle uses BNY Mellon for such services in relation to USDC. Thusly, the custody agreement Mr. Taibbi highlighted here has nothing to do with GUSD reserves. (Noting further that Gemini outsources the money market portion of its reserve management to Goldman Sachs Asset Management.)

Below is the custody section of Gemini’s user agreement that Mr. Taibbi referenced, noting it specifically relates to digital assets rather than fiat.

Further down the agreement comes the fiat custody portion, whereby Gemini specifies that fiat is held in omnibus bank accounts in its name and under its control. Gemini further notes that each GUSD “corresponds to one U.S. dollar held across one or more omnibus accounts.”

So similar to USDC being the sole beneficiary of the Circle Reserve Fund, so too is Gemini the sole owner of these various omnibus accounts established to manage its GUSD reserves (and presumably the beneficiary of that Goldman money market fund). Some cover is achieved when Gemini specifies that those accounts are established for the “benefit of Gemini customers”. But Circle’s user agreement says the same thing.

Third - while admitting I’m no expert on bankruptcy remoteness - my understanding is that trust agreements are not in and of themselves evidence of such. Bankruptcy remoteness addresses the segregation of one entity’s assets from those of other entities within the same group to limit the reach of creditors. In the case of Paxos, it appears that the issuer of its stablecoins also acts as the custodian of its reserves (i.e., both functions look to be performed by the same legal entity, Paxos Trust Company, LLC).

Elsewhere on its website, Paxos states that its reserves are held in fully segregated, bankruptcy remote accounts. No further clarification is provided as far as I can tell, which appears good enough for Mr. Taibbi. I have no reason to dispute the company’s claim - especially given its strong reputation and focus on regulation - but the quote Mr. Taibbi included here fell short of providing evidence that anything was “truly bankruptcy remote”.

Lastly, the referenced quote from Paxos is incomplete. The company’s statement actually reads that its stablecoins are “fully backed by U.S. dollars…or by debt instruments that are expressly guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the United States Government and/or money-market funds composed of such debt instruments.”

Circle happens to say pretty much the same thing: “The USDC reserve is held entirely in cash and short-dated U.S. government obligations, consisting of U.S. Treasuries with maturities of 3 months or less.”

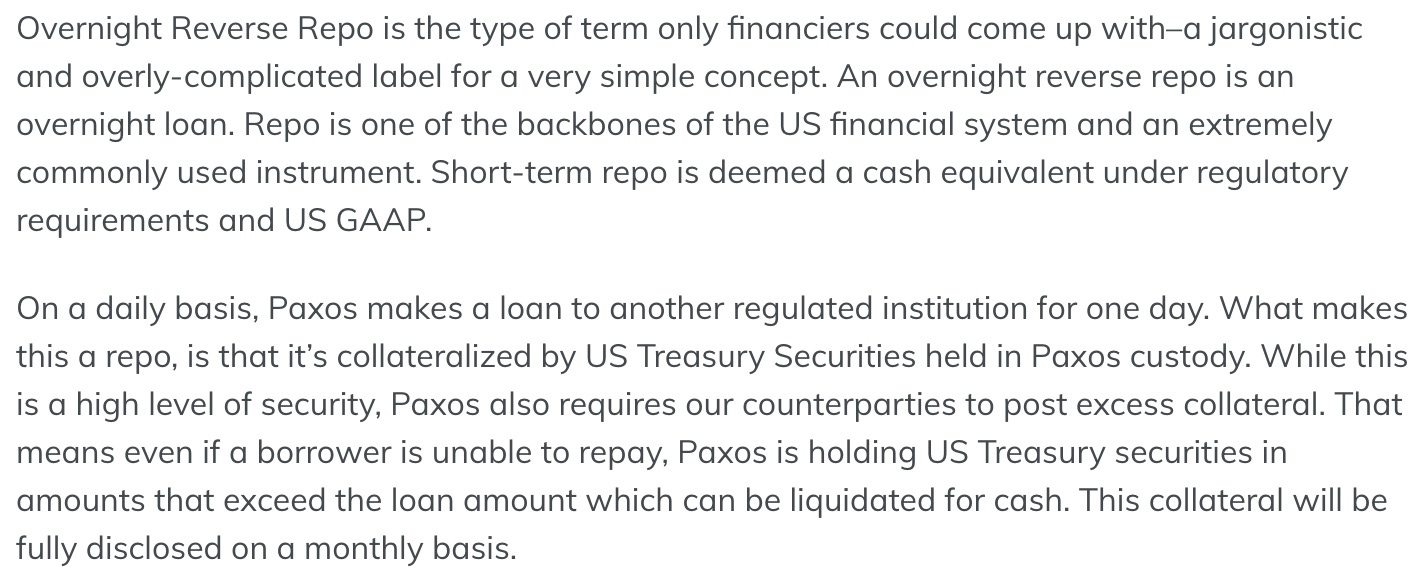

Mr. Taibbi also expressed concern that Circle’s reserve fund could invest up to a third of its assets in reverse repurchase agreements (reverse repos).

Also, the new fund would be “permitted to invest up to one-third of its total assets in reverse repurchase agreements.” Would Circle be making use of that provision?

Regarding the BlackRock fund’s provision allowing them to borrow up to a third of the reserves, I learned that government money market funds typically do not borrow, but also that the company would enjoy access to the Fed and its repo borrowing program.

Repurchase (repo) agreements basically involve one party selling securities to another with an agreement to repurchase those assets shortly thereafter at a predetermined, higher price. Repos and reverse repos are basically opposite sides of the same borrowing and lending coin. These are typically overnight and overcollateralized arrangements, making them low risk in nature.

It’s unclear why Mr. Taibbi is concerned here as repos are common short-term liquidity and investment instruments. They are in fact a mainstay of money market investment programs. Per Barclays, “repo allocations from government money market funds have increased to nearly 40% of their assets currently.” The SEC even released a primer last year discussing the outsized role money market funds play in the repo market.

Paxos, which is among the most regulated crypto firms, already makes regular use of these instruments for its own stablecoin reserves. In fact, roughly a third of the reserves associated with Binance USD (BUSD) - which at $18 billion is by far the company’s largest stablecoin offering - is invested in reverse repos.

The company explains its reverse repo activities in some detail on its website:

Investing in reverse repos is thusly far from a controversial practice. Granted, Circle could theoretically be on the borrowing end of these agreements, which I’m guessing is the concern for Mr. Taibbi. But it stands to reason that stablecoin issuers would avail themselves of all manner of short-term liquidity instruments to manage their reserve flows.

We see such flexibility afforded to traditional money market funds as well. For example, Fidelity manages one of the largest government money market funds in the world, the $250 billion Fidelity Government Money Market Fund (SPAXX). Its prospectus specifies that the fund may enter into reverse repurchase agreements, even to “satisfy redemption requests”. These funds may not “typically” make use of such provisions, but the ability to do so is there, same as with the Circle Reserve Fund.

Mr. Taibbi later asked Circle where its reserves were held, to which the company responded with a list of banks holding its cash reserves and the custodian responsible for its Treasury purchases. That answer was not good enough for Mr. Taibbi:

This is a non-answer. Circle discloses where some of its reserves are, but not all, and not how much of what is where. Now, Circle separately features a Yield program, which offers guaranteed returns. These were never as high as Terra’s preposterous and obviously Ponzoid 20% guaranteed returns, which quickly attracted $60 billion that vanished even more quickly, but the program exists nonetheless, at one time offering 12-month yields as high as 10.75%…In the time it’s taken to write this piece the guaranteed return has dropped from 6% to 1% to 0.5%.

This response is some combination of unfair and uninformed. Circle answered the question that was posed to it. No stablecoin issuer provides an exact breakdown of its counterparty arrangements, likely in an effort to protect its partners and users. As of its latest attestation - which predates Mr. Taibbi’s post - Circle’s reserves are currently 100% cash and Treasurys, so the company answered where all - not some - of its reserves were held.

Mr. Taibbi also demonstrated misunderstanding of crypto markets when mentioning Terra, the blockchain responsible for the failed stablecoin UST and home to a number of other projects. One of those projects was a savings and lending protocol called Anchor, which at one point offered yields as high as 20%. At its peak, Anchor had about $20 billion in total deposits. Terra’s native token, Luna, had a peak market capitalization of roughly $40 billion prior to the depegging of UST.

So yes, roughly $40 billion in user capital “vanished” amidst the UST meltdown as the price of Luna fell from about $100 to nearly $0. But only $20 billion of user capital was related to the “ponzoid” Anchor product. And not all of that was lost since plenty of the drawdown in Anchor assets simply involved users removing their deposits from from the protocol as UST depegged. Real money was certainly forfeited in that process but nowhere near the full $20 billion worth.

And use of the term “guaranteed” here is bogus. Nowhere on the Circle or Anchor websites is that word used in relation to their offered yields.

When Circle announced that it would allow its Circle Yield (CY) customers to withdraw funds penalty-free as crypto markets plummeted, Mr. Taibbi responded skeptically with, “make of that what you will.” Huh? The only thing to make of such a move is that Circle was operating from a position of strength by offering its customers early liquidity in a period when such liquidity was evaporating elsewhere.

Mr. Taibbi commits a fallacy of composition by mentioning CY in the same breath as Anchor, like all yield is bad yield in crypto. To do so is wildly off base as these are entirely different products. Anyone could deposit any amount in Anchor whereas CY is built more for institutional accredited investors with a minimum investment of $100,000. And the yields on offer with Circle are much more rational in a market context whereas the Anchor yields were clearly artificially manufactured.

Mr. Taibbi then made the following statement in response to Circle stating that it does not use USDC holders’ money to run its business or pay its debts:

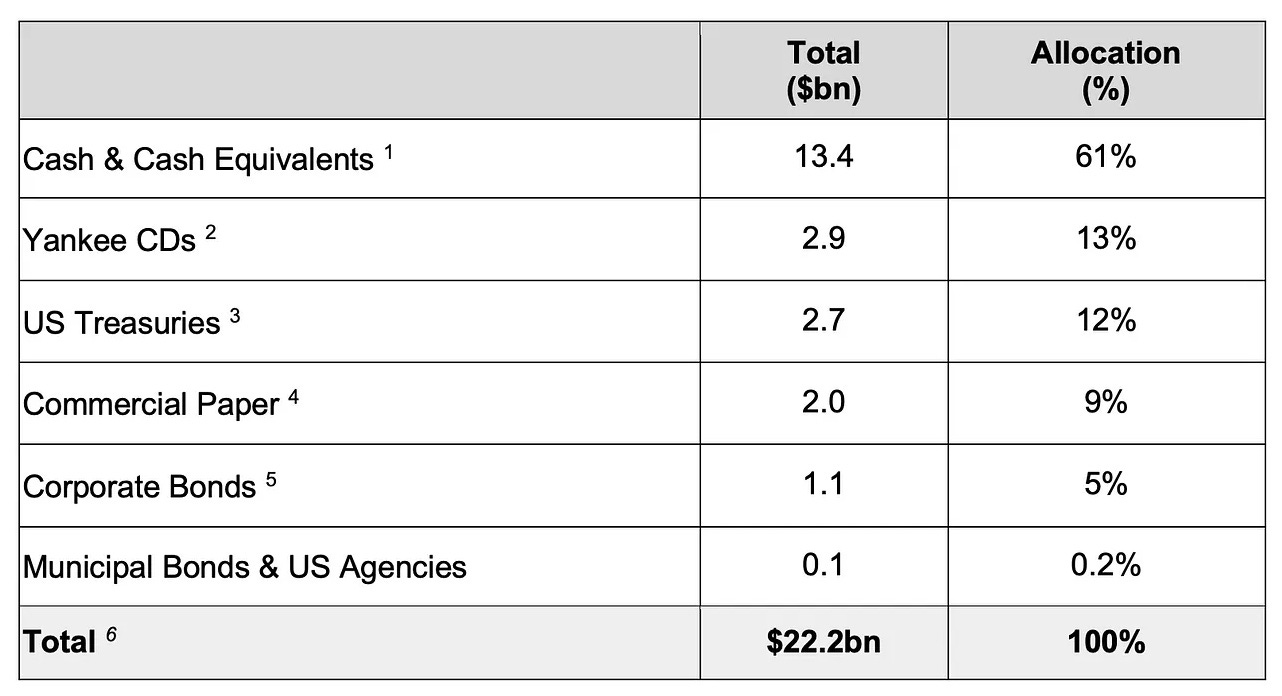

If Circle does not and will not use USDC holders’ money to run its business, how is it projecting to earn $438 million in revenues from its USDC reserves this year, and over $2.188 billion next year? Again, is USDC a utility-like product content to earn little caring for giant piles of money, or more like a profiteering financial firm that earns money creatively leveraging up its assets? This raises another question that first came up last year. If Circle is holding its reserves in segregated accounts strictly for the benefit of customers, why was it, at least at one time, keeping a not-insignificant portion of its reserves in commercial paper and instruments like Yankee CDs?

Mr. Taibbi demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of the stablecoin business here. The primary economic objective of a fiat-backed stablecoin is similar to that of a money market fund. With the latter, investors can earn yields in excess of interest-bearing bank accounts by allocating to a fund that invests in relatively safe, short-term debt instruments to generate some extra yield. Circle effectively does the same with its USDC reserves.

However, instead of any incremental yield going to investors like with a money market fund, that spread is instead captured by Circle. This is possible because holders of USDC are not expecting any gains to accrue to them. They simply want to know they can redeem their USDC at any time for $1.

So what Circle is saying here is that it doesn’t take the $1 that someone uses to purchase USDC and deploy that $1 to pay its own bills. It instead tries to turn that $1 into something like $1.0075 and keep the incremental $.0075 as revenue.

Circle’s revenue projections on USDC reserves therefore make sense. USDC market capitalization has exploded over the past year. If we extrapolate that growth through yearend and assume a blended yield of 0.75% on its USDC reserves, we get to the revenue Circle has projected for 2022. The company has obviously taken some liberties with expected growth in USDC demand as well as interest rates with its 2023 projections, but it wouldn’t be the first company with listing aspirations to get aggressive with its financial models. Besides, with 3-month T-bills currently yielding 2.4%, its assumptions might not be that aggressive after all.

So yes, Circle is quite content to “earn little caring for giant piles of money”. That’s because this a volume business in the same way Vanguard is happy to charge bargain basement fees on its trillions in assets under management. In this type of setup, there really is no need to “creatively” leverage up its assets. Nor is there evidence of the company doing so. In reality, the bigger USDC gets, the less incentivized it is to reach for yield. This is especially true in a rising interest rate environment where the ball can do the running for you (to steal a soccer phrase).

Mr. Taibbi then focused on Circle’s July 2021 reserve attestation, noting “a surprisingly high amount held in riskier or less liquid investments like corporate bonds and commercial paper.”

Firstly, the chart Mr. Taibbi references is from Circle’s May 2021 attestation, not July 2021. Second, risk is a spectrum. Everything listed here outside of cash and Treasurys is relatively risky when compared to risk-free but not necessarily risky in absolute terms. Yankee CDs are similar to regular certificates of deposit, which are among the least risky investments one can find outside of Treasurys. The main difference is that they are issued by the US branch of a foreign bank. Think of names like Barclays, Santander, Scotia Bank - not exactly fly-by-night enterprises.

Commercial paper is generally considered low risk given its short-term nature and corporate bonds are only as risky as the credit ratings attached to them. The footnotes Mr. Taibbi excluded note that Circle’s corporate bond portfolio was comprised of credits rated a minimum of BBB+. This qualifies as investment grade per S&P’s ratings guide (i.e., low risk of default), which contrasts with the quality of paper rumored to plague the likes of USDT.

More to the point is that most of this handwringing is moot. Per a July statement, 80% of USDC reserves are in US Treasury instruments of durations of three months or less with the remaining 20% held in cash. This makes total sense. With due respect to the Circle management team, USDC has morphed into a cash cow business that should be on cruise control and involve little brain damage as it relates to its reserve management. Throw the yieldy stuff BlackRock’s way then put the rest in the bank and call it a day. Set it and forget it while generating hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue thanks to a growing numerator and denominator. This is a fantastic business that is far from rocket science. You’d have to be an idiot to screw it up.

Mr. Taibbi went on to lament the fact that Grant Thornton (GT), the accountant who conducts regular attestations of USDC reserves, tweaked some language in its attestation reports from “correctly stated” to “fairly stated”. The insinuation being that GT is making the language more equivocal - presumably due to concerns it may have with Circle’s assertions - when in reality GT was simply adopting verbiage more conventional to the industry.

He then complained that the most recent attestation used “the word ‘opinion’ four times and ‘audit’ zero times.” This is a strange complaint since an attestation is technically a type of audit whereby a professional accounting firm provides an opinion as to the reasonableness of presented data. Paxos also conducts regular attestations of its stablecoin reserves, with the most recent mentioning “audit” just once (to effectively say the attestation was not an audit) and “opinion” seven times.

He also made the following odd comment: “Grant Thornton did not respond to requests for clarification as to whether or not they consider these reports audits, though the company, Circle, considers itself audited.”

Of course GT doesn’t consider those reports to be formal audits. Because they’re not. They’re attestations. And Circle doesn’t consider itself audited. It is audited, having engaged one of the top IPO audit firms, Marcum LLP, for such services. This is a critical step for any company seeking to list on a public stock exchange.

Mr. Taibbi went on to question Circle’s status as the “good crypto” by first noting its delay in securing a bank license and then rehashing its CEO’s questionable past.

Four years after it first declared its intention to be the first coin with a bank license we’re still reading headlines like, “Circle Will Apply for U.S. Crypto Bank Charter in ‘Near Future,’” in the hopes now of becoming the fourth stablecoin to get licensed. The company does not believe current law allows it to become a bank, but similar companies didn’t seem to have had a problem.

Mr. Taibbi is again confusing things here. Coins don’t get bank licenses, companies do. There are three other crypto companies that have been provisionally approved for bank charters - Paxos Trust Company, Protego Trust Bank and Anchorage Digital - but only one of them has issued a stablecoin (Paxos).

What he may be referring to instead is the fact that there are three stablecoins that are subject to oversight from the New York Department of Financial Services: Gemini’s GUSD and Paxos’ USDP and BUSD.

Mr. Taibbi finished his piece by putting Circle Cofounder and CEO Jeremy Allaire under the microscope, drawing attention to a fraud allegation that he settled 20 years ago relating to a previous company of his, Allaire Corporation. Though no wrongdoing was admitted, one can only assume the implication here is that Circle is not to be trusted given the checkered past of its leader. The involvement of former Barclays chief executive, Bob Diamond, in Circle’s upcoming SPAC only exacerbates the issue for Mr. Taibbi.

I have no idea whether Circle is full of shit when it comes to its attestations or whether USDC reserves are held in truly bankruptcy remote accounts. I don’t know if Circle might have been - or could be in the future - negligent when it comes to managing its reserves. And I have no insight into Mr. Allaire’s character or the manner in which he runs his firm.

What I do know is that Mr. Taibbi has built the flimsiest of cases with this piece, which I’m afraid will be read by his less discerning readers and taken as gospel as it relates to Circle’s guilt. Mr. Taibbi may ultimately be proven correct to have casted a wary eye towards the likes of Circle, but that won’t make his post any more accurate in its treatment of the firm and the broader stablecoin business.